Thomas Jane’s Love, Lust & Lycanthropy

- Rich

- Apr 16, 2025

- 24 min read

In sharing the “Top 5 Werewolf Movies” that inspired Renegade Entertainment and ComiXology Originals’ new comic book mini-series The Lycan, actor Thomas Jane digs deep into the lore and mythology of these magnificent beasts.

Lycanthropy: from modern Latin lycanthropia, from Greek lukanthrōpia, from lukos ‘wolf’ + anthrōpos ‘man’.

“Beware the moonlit path, for it is the playground of the werewolf, where it hunts with a hunger that knows no bounds.” — Stephen King, Cycle of the Werewolf (1983)

What is it about the werewolf that makes it such a powerful cultural icon? Studying “the animal” we understand the wolf is a pack hunter, while human nature tends to follow a herd mentality. We depend on the herd for our survival — whether it is the animals that sustain a village or the villagers themselves — and when this is threatened by a cunning hunter, we risk losing everything. The wolf lurks at the edges of the herd, stalking those who stray from well-trodden paths. However, while wolves hunt in packs, the werewolf is a lone hunter. Part man, part beast, it is left to its own devices and threatens to destroy us not only by bloody violence but by the fear and panic of this “wolf/man” running amok. A hybrid that has, over centuries conjured an extremely powerful and potent image. Iconic, for sure.

Typically (but not always) male, the werewolf is a virus of violence and lust disguised as a normal citizen, a wolf in sheep’s clothing that threatens to destroy what we have worked so hard to create: a civilized society of civilized men built to protect our most valuable assets: our women and children. In short: the werewolf is the beast in mankind that wants to destroy everything we love…

Fuck the Rules: A Prelude to Werewolfery

In medieval Europe, the werewolf legend became intertwined with witch hunts and superstition. People believed that certain individuals could shapeshift — often as a result of curses or a pact with the devil — and it wasn’t long until the fear of werewolves surged, particularly in the regions of France and Germany as numerous trials and executions were conducted in the name of eradicating these purported monsters. It was merely another witch hunt.

Left: A woodcut print by Lukas Mayer based on the execution of Peter Stumpp in 1589 at Bedburg near Cologne. The case led to a peak in werewolf trials based on accusations of lycanthropy (an individual transforming into a wolf) or the more believable wolf-charming and wolf-riding. Right: Georg Kress's woodcut of the She-Wolves of Jülich, Germany, 1591.

Within the modern world, our fascination with the werewolf still cuts deeply into our souls in a couple of different ways. While other monster movies typically revolve around humans running from an evil creature, the typical werewolf story revolves around the monster itself as the star of the show. This cursed hero is the outsider in society; the stranger in a strange land who finds himself surrounded by familiar, yet alien people and societal structures that we are obligated to follow in order to become a valid member of the community and, in the grander scheme, part of the human race.

Everybody wants to blend in and be accepted, but there are unspoken rules and mores that we all take for granted (often remaining unconscious); your ability to learn and follow the rules a test of your social status and acceptance. In Europe, such mores used to be very structured; if you held your fork in the wrong way, you would be ostracized from the group as either ignorant or socially inept. If you purposefully flouted what other people had spent so much time and energy perfecting, it made you an asshole — an outsider. Today we are not as structured, but to break the rules or ignore them still comes with a heavy social fine that nobody wants to pay. So, the werewolf expresses the rebellion, denial, and the ultimate futility of playing by the rules and mores that everyone put so much stock in. The lower classes didn’t have time to be educated with all the etiquette and other strict disciplines, which could be everything from the way you folded your napkin at the dinner table to the quality of the “calling card” used to introduced yourself… even down to how you held the door open for a “lady.”

The average citizen may be able to fake it for a while — scrape together a decent suit, shine their shoes and cut their hair in the latest style to blend into a polite society — but the werewolf has been cursed; either through fate or moral transgression, the irrepressible werewolf shattering the facade of it all and then, by default, exposes you as “the other,” “the Outsider!” — especially when (if respecting any lore) there is a full moon. You can run, but you can’t hide from the mark of the beast.

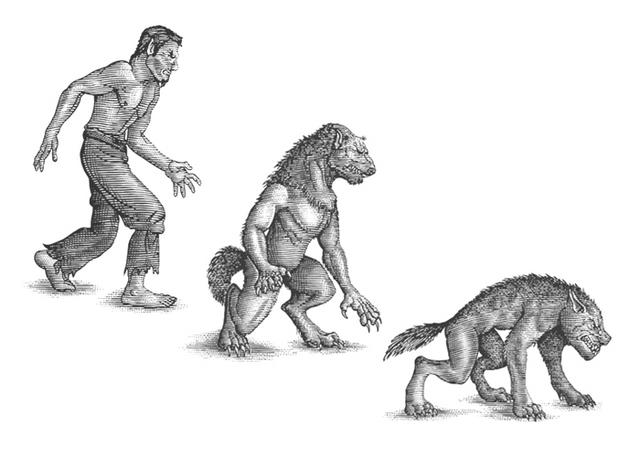

Charles Darwin's The Origin of the Species (1859) completely changed society's perception of our relationship to the animal kingdom. Now there was a realisation of evolution and literature of the time reflected this, such as Robert Louis Stevenson's 1886 novella The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. Transforming into a wolf was not that "wild" an idea after all. Art by Steven Noble.

Secondly — reminding myself of Walter B. Gibson’s The Shadow — it is all about “what evil lurks in the hearts of men [and women]” — the reveal of the animal… the beast… the lust and the violence that we work so hard to suppress. And it lurks inside of everyone. Ever since Charles Darwin pointed out the inescapable fact that our “origin” and our “descent” is our common ancestor the ape, the defining mark of humanity has become about the ability to control our animalistic inner nature to the benefit of the people we love and society at large. We are judged by our ability to control the animal because that is basically what we are. The wrestling of these aspects — the outsider and the animal — which are interrelated but distinct, means that the beast bleeds in and will never follow the mores of a dinner party or any other rules that are meant to keep mankind under control.

This is why the werewolf strikes a chord with everybody. Of course, the stories are mostly male dominated, because it is often about the male dealing with his anger and his lust. For women, it becomes about a different transformation; the inevitable coming-of-age, marked by a monthly cycle that may play into a natural inclination towards stability. This is where their conflict lies: honoring the feminine aspects of purity and innocence while negotiating the turbulent world of men. In fact, we could say that it is probably the female that has given us the reason for society to civilize in the first place; a lot of civility deriving from our desire to protect, nurture, and honor femininity in our society. With this in mind, you could say that women are civilized and men are being civilized.

Classic monsters represent the worst in us all. From a purely alpha perspective, the werewolf remains the hetero, whereas the vampire (often its antithesis) remains androgynous and gentrified; something more evolved than devolved. Both are animalistic, but where the werewolf is about discarding the rules — in favor of base instinct and momentary desires — the vampire accepts and manipulates them in order to blend into and eventually control society. They become the aristocrats or exploit them from behind the scenes… or even from beyond the grave. They are, by default, more “polite,” more political, and, therefore, more insidious in trying to either control or destroy humanity. The Vampire is still able to think like a human and in their natural evolution have tended to reinvent themselves over and over again, often becoming a master who enslaves… while the werewolf remains chained to its bestial mark. As degenerate characters, the act of rape may also play into these films. Whereas the vampire is a seducer — it must be invited in to work its irresistible charms — the werewolf destroys all boundaries; there is no consent: it will huff and puff and cave your house in… and tear you apart.

THE LYCAN is written by Mike Carey, based on a story by by David James Kelly (Logan) and Thomas Jane, and illustrated by Diego Yapur. Slide through for a "taste" of the pages.

Throughout the 20th century, werewolf lore has often been modernized — especially via Hollywood — and tended to lose sight of its roots. In creating my comic book mini-series, The Lycan, it was all about going back to a more traditional approach. The werewolf tale can take many forms and follow many paths, so I have created a list of five favorite werewolf movies based on how they relate to The Lycan, which is, at its heart, a gothic horror that revolves around the transformative and destructive power of love. As great as a physical transformation is — and all of these films have them — this list is more about how love and lust either transforms or destroys the savage beast.

Each film specifically relates to our take on the subgenre in which we played with the mythology; acknowledging those tropes and conventions created by Hollywood but also going back to pre-Hollywood with the European legends. And so, the period in which our tale is set is the end of the Old World and the beginnings of an independent “Untied States” breaking away from the Empire. This important transition of Western civilization is seen as a battle between newfound possibilities and unshackling ourselves from the rules of the past. At its best, society allows a collective to work together to achieve great things… and at its worst, it becomes the cage that shackles our creative instincts and natural drives. As already highlighted, the werewolf is the perfect monster to explore all of this because it is connected to the sculpting power of society and its “wolves” within… where the individual battle between our fears and our desires lies.

5.

Werewolf of London (1935)

Predating 1941’s The Wolfman — and celebrating its 90th anniversary on May13th — Universal’s first werewolf feature is the origin of most of our modern werewolf mythology. In the original stories from Europe, a man or woman usually changes into an actual wolf and then back again but in 1935 we have the beginnings of the werewolf legend that has since crossed over into popular culture. Indeed, the idea that if you are bitten by a werewolf and then change into one under the full moon begins here, whereas before, in European mythology, it was down to witchcraft; a sorcerer or witch who deliberately transformed themselves so they could do things in society they wouldn’t be able to do as a human being. You turn into a wolf, kill the person you hate, and take what you want… and no one would be the wiser; the bourgeoisie assuming the person had been killed by a wild animal.

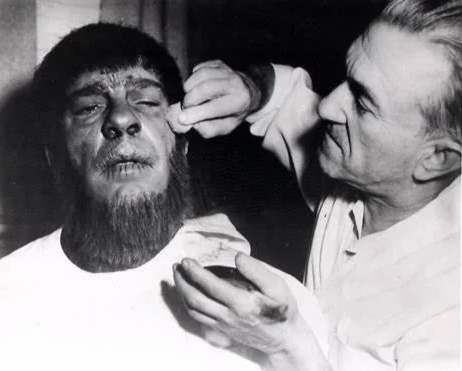

Directed by Stuart Walker, in Werewolf of London we are presented with the monster we have become so familiar with over the years. Created by the legendary Hollywood make-up artist Jack Pierce who helped bring to life the Universal Monsters in 1931; the banner year that unleashed Tod Browning’s Dracula and James Whale’s Frankenstein on audiences. Along with Karl Freund’s The Mummy the following year, they were massive hits and instantly burned into our psyche, Pierce was now presented with the challenge of creating the first “Wolf Man” in the lead, Henry Hull. Although the majority of Hull’s earlier films from 1917 to 1925 were all lost silent movies, as a huge Broadway star — when Broadway actually meant something — he had now gained more attention; his screen work finally taking off starring in Midnight alongside an up-and-coming Humphrey Bogart in 1934.

A fierce looking Henry Hull under Jack Pierce's first werewolf design.

When Jack Pierce was developing make-up effects, the story goes that Hull complained that the design was too hairy and that the audience wouldn’t know it was him. So, the studio convinced Pierce to tone it down so the character of Wilfred Glendon could be recognized, which, it must be said, was part of the story; the other characters recognizing Glendon when he transformed. This is the original “pompadour” werewolf, later used to great effect in 1957’s I Was a Teenage Werewolf and John Landis’ groundbreaking An American Werewolf in London from 1981, which modernizes (and lampoons) Universal’s own Lycan legacy. [1]

Warner Oland also stars in the film who, at the time, was famous for playing the Chinese detective, Charlie Chan. A severe alcoholic, his rages would often result in him storming off sets. Subsequently he died in 1938 during the production of the 17th Charlie Chan movie, which was never completed. This reminds us of another interesting parallel with the werewolf: a Jekyll and Hyde aspect of an overactive id — the drink and drug use that unleashes different aspects of the animal you are unable to control.

The story begins with Glendon, a botanist who has spent months in Tibet searching for a rare flower that only blooms under the light of the full moon, located in a dangerous valley no man has ever returned from. He meets an old padre along the way who warns him not to venture further, telling Glendon, “You are foolish, but without fools, there would be no wisdom.” He heads into this “Valley of Demons” and the moment he finds the very thing he has been searching for… a shadow looms and the werewolf attacks.

A shadow looms as a flower blooms.

Bitten, he returns home with the precious moonflower. Holed up in his laboratory, he experiments to find a way of helping the moonflower bloom under artificial moonlight, but also succeeds in accelerating his lycanthropy. He is deeply in love with his wife and, as a botanist, wants to finish his research so that he can rejoin polite society. Dr. Yogami (Oland) stops by and reveals that the flower happens to be the only known cure for “werewolfery” — a term I’m particularly fond of. Yogami — of the University of Carpathia, I’ll add — is an expert; going on to explain that in modern London today there are two cases of werewolfery known to him, both caused by the bite of another werewolf, adding the indelible line: “The werewolf is neither man nor wolf, but a satanic creature with the worst qualities of both.”

Crucially, Yogami tells Glendon that “The werewolf instinctively seeks to kill the thing it loves best.” After all, the reason for civilizing is to protect women and femininity; while Glendon the man searches for a flower that is the ultimate symbol of beauty, grace, delicacy, and love… Glendon the werewolf instinctively wants to destroy all of it.

4.

The Wolf Man (1941)

In the Golden Age of Hollywood, the old factory studio system was working overtime. A rushed production, Universal’s next werewolf feature The Wolf Man was still shooting up until two weeks before its release and, to make matters worse, was released just five days after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

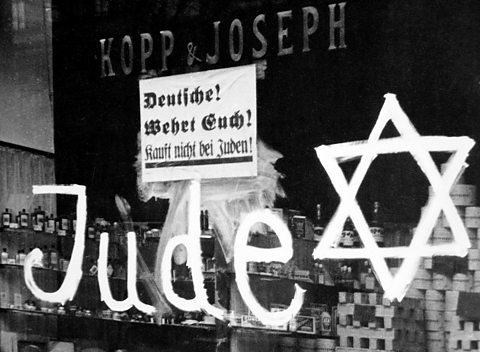

George Waggner directs with a keen eye for atmosphere, but it is screenwriter Curt Siodmak’s script that provides not only a solid foundation but the key ingredients in pushing werewolf lore further. As a Jew he brought in an all-important outsider element, his skills as a novelist developing a script that layers in all manner of subtext and symbolism such as the inversion of the Star of David that takes on the form of a pentagram, marking the werewolf’s next victim. All of these details tell the story of Siodmak’s journey out of Europe and, as with any good writer, used the antisemitism he witnessed and shaped it into something extremely compelling — “Hounded; on the run; this was his own curse…” [2] — his own religious symbol (and identity) demonized by the Nazis. It’s all echoed once again in An American Werewolf in London 40 years later as Nazi stormtroopers appear as hounds of hell to massacre a Jewish family in their home. [3]

Another major addition to the mythology was adding silver to the mix. This may have had its roots in European literature where all manner of creatures were killed by silver bullets, from Swedish folklore to the Beast of Gévaudan — a man-eating animal apparently killed by the hunter Jean Chastel in 1767. Historically, silver is a symbol of purity and protection; the Greeks and Romans believing silver possessed magical properties. Here it is the silver wolf head that adorns a cane, which our hero Larry Talbot (Lon Chaney Jr.) picks up while attempting to seduce a young paramour.

The powerful use of the pentagram that demonizes the Jew. An explicit reminder of their persecution during this period.

There is an interesting lineage here; not just in the central character and his father but, of course, Lon Chaney Jr.’s own father Lon Chaney Sr. Affectionately referred to as “The Man of a Thousand Faces,” he was absolutely instrumental in those formative years of Universal horror, with the revolutionary make-up effects he created and applied to himself for such knockout performances in The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923) and The Phantom of the Opera (1925), to name a few. Jack Pierce learned directly from Chaney Sr. and now, working with Jr., they were to create another iconic Universal monster.

Jack Pierce applies the iconic make-up effects to Lon Chaney Jr. The end result is iconic, to say the least.

In The Wolf Man Larry Talbot is an outsider from America who comes back to his father’s estate in London — which has been in the family for five generations — returning to his roots, as it were. [4]. Developing the lore further for the modern age, Siodmak considers Lycanthropy “a disease of the mind,” hinting at the psychological devices that films of the ‘40s became known for. However, much like those traditional aspects we reach for in The Lycan, this film still manages to capture a timeless fairy tale quality set within an almost alternative Europe. There is a poetry to it and in Patrick McGilligan’s Backstory 2 from 1991 an interview with Dennis Fischer [5] captures Siodmak reflecting profoundly on his own work:

It even goes much deeper than that, though I didn’t know that when I wrote it. One day many years ago, I got a letter from a Professor Evans from Augusta College in Georgia about the parallel between The Wolf Man and Aristotle’s Poetics, which is a critique of Greek plays. I thought the guy was nuts. Not true. In the Greek plays, the gods reveal to man his fate; he cannot escape it. The influence of the gods over man is final, and that’s like the domineering father the character has in The Wolf Man. He knows that when the moon is full, he becomes a murderer. That is his preordained fate. The film was constructed like a Greek tragedy, without my intent at the time, but it fell into place and that’s why it has run for forty-eight years. (McGilligan, p.258)

Hendrik Goltzius' engraving Lycaon Changed into a Wolf (1589).

Even through osmosis, this element of Greek tragedy at the heart of The Wolf Man — that the beast must be killed by the father — is a nod to King Lycaon who, in the most popular version of the myth, killed and cooked his son Nyctimus and was then transformed into a wolf by Zeus after Lycaon offered the god human flesh. The relationship between father and son is paper thin here, the aforementioned tragedy illustrated in more bloody detail in Joe Johnston’s 2010 remake, The Wolfman as father and son tear into each other during the fierce climax [6].

Here, there is no sinister relationship. When we see Larry with his father, Sir John (Claude Raines) he fixes his telescope… and of course, we bypass all the astrology and potential lunar references as Larry then spies on the love interest Gwen (Evelyn Ankers). This all leads to him flirting with her at an antique store where he purchases the silver wolf-headed cane that happens to be also inscribed with a pentagram. He takes Gwen and her friend (because she’s a good girl engaged to be married) to the gypsy world (as you do)… already moving her off the beaten path through a fog-laden forest. Here the details of the gnarled trees and gravestones near the outsider zone where these travellers hang are captured with a wonderfully evocative atmosphere that adds to this short journey into the night. This “straying from the path” is echoed throughout many werewolf movies, society marking the routes we must follow.

And it is love, or lust, that is Larry’s downfall. When Gwen’s friend is marked by the pentagram, a Gypsy fortune teller (Bela Lugosi) freaks out and within minutes she is ripped apart by a wolf and killed. Larry arrives too late, is bitten, and then beats the wolf to death with his silver cane. Of course, the body of the fortune teller is found in the animal’s place and the cops put the death of the woman down to murder as Larry is unable to prove he has been bitten by a wolf in the attack. With his bite mark already vanished, his werewolfery is further fuelled by his love for Gwen, who is engaged to a socialite. As he fights the curse, a Gypsy woman Maleva (Maria Ouspenskaya) regales us intermittently with a poem scattered throughout the film:

Even a man who is pure in heart

And says his prayers by Night

May become a wolf

When the wolfbane blooms

And the autumn moon is bright.

The poem reminds us that the mythology of the werewolf is well established and so the people in our story understand the dangers of straying from the path and being attacked and killed by wolves… who may or may not be human beings.

3.

The Curse of the Werewolf (1961)

In Oliver Reed’s first starring role, this is Hammer at its best. I often wonder if we were to have had this film a decade later with Reed on the cusp of greatness and riding his “hellraiser” notoriety, The Curse of the Werewolf would have been a very different film; perhaps a little less Terrence Fisher and more Ken Russell… more “devilish”… and all the more censored. Speaking of censorship, the film lands at an interesting time with the BBFC having become more and more alarmed with Hammer’s output. In addition to the release of Psycho (1960) and Peeping Tom (1960) the previous year there was apparently a great deal of backlash against the BBFC for their lack of action. With stricter rules now applied, Hammer Studios was seemingly made an example of.

Hammer had been set to produce a film about the Spanish Inquisition — specifically based on The Rape of Sabena — and had already built the Spanish sets in Berkshire, England. Unfortunately, such subject matter needed approval from the Church back then, which they ardently refused. So, Hammer scrapped that film and decided to set their adaptation of Guy Endore’s 1933 novel The Werewolf of Paris in 18th century Spain to take advantage of the Spanish sets. Then the BBFC threatened to ban Curse of the Werewolf if the film went ahead as written. Hammer decided to ignore the BBFC, resulting in severe cuts to the film and damaging its box office results, so it wasn’t until the scenes were restored during the ‘90s that The Curse of the Werewolf was seen in its full glory.

Richard Wordsworth as the Beggar is reminiscent of the figure in Lucas Cranach the Elder's 16th century woodcut The Werewolf or the Cannibal, which is often used as a point of reference when delving into the origins of Lycanthropy.

Another key change they had to make was the origin story of the werewolf. As a period-set horror, the story does not rely on the bite of another werewolf, but something born into. Again there is the aristocracy and decadence and, in contrast, we see a beggar imprisoned by a cruel marquess after he insults him at his wedding feast. Trapped for years, the only contact he has is the mute daughter of the jailer who eventually grows into (as expected in a Hammer production) an extremely sexy woman. The Marquess, having lost his mind after the death of his wife, attempts to rape the girl, and when she manages to get away he throws her in the dungeon with the beggar — who has now been driven insane by his isolation.

Originally the beggar was a werewolf but in consulting the Church they were told: “You can have a werewolf, or you can have a rape, but you can’t have a werewolf raping the servant girl.” They went with rape, which is implied, but the beggar is not a werewolf; he is just… well… more hairy. When the Marquis attacks the servant girl a second time she kills him and runs off where she is eventually found face down in a river by a well-to-do man Don Alfredo Corledo (Clifford Evans). Discovering the girl is pregnant, he allows her to stay.

Her baby is born, of all dates, on Christmas day, which in European mythology is a really bad thing as it was believed that such a child was competing with the assumed birth of Jesus Christ and that the curse was a punishment for blasphemy -— like you have any control over the day you are born. Adopting the family name of the Don, the child-of-rape-by-a-madman Leon Corledo enjoys the taste of blood… and the sheep in the village start to go missing. The kid grows up to become Oliver Reed and goes to work in a winery and wrestles with his demonization as a love tryst begins to bring out the worst in him when he falls for a woman who is to be married to another “rich dude.”

Roy Ashton's make-up design for Oliver Reed made the most of his strong features, further embracing a lupine influence.

In this story, the werewolfery is no fault of the afflicted. Leon is a child of rape born under a bad sign — a fate that casts our hero outside of society and into the depths of hell. It is lust and debauchery and a full moon that brings things to head in this story… and, once again, it is the father who must, in the end, kill the son, suitably in the Belfry of a church tower. With all of this in mind, there is something puritanical and so, unlike The Wolf Man and its Jewishness, The Curse of the Werewolf is, instead, deeply entwined with Christian mythology. As a period set piece, these major themes of the film were a particular touchstone for us on The Lycan, especially when looking at how legend, mythology, and religion intertwine.

2.

The Company of Wolves (1984)

Directed by Neil Jordan and co-written with Angela Carter — whose short story it is based on — The Company of Wolves is a smorgasbord of nightmares. It is a film I didn’t particularly appreciate at the time because it was a “woman’s picture” — a story for girls and the coming of age; the loss of innocence and all of those crucial fairy tales that are interrelated that obviously draw heavily from Little Red Riding.

A huge inspiration on The Lycan; the fairy tale for adults aspect and the feminine power within a male world is a particularly powerful theme. There is nothing more pure than these kinds of tales; a young innocent on the cusp of womanhood navigating her way through this adult world of sex and danger, of masculinity and animal nature. It is full of evocative and dreamlike imagery such as the central character of Rosaleen (Sarah Patterson), running through the woods and being chased by a pack of wolves. In this version of a familiar story, her red cape, knitted by her grandmother, becomes an even more explicit symbol of the feminine cycle, the film wearing its symbology on its sleeve, from the innocent white dress to the splash of scarlet to tiny human babies hatching from eggs.

Granny (Angela Lansbury) prepares Rosaleen (Sarah Patterson) for the dangers in the world.

Rewatching it as an adult there was far more to enjoy and appreciate with all the fantasy elements providing a dark fairy tale with all the trimmings. I love the flora and the fauna of it all; the oversized mushrooms and a Grimm forest of our imagination. It feels like our dreams and nightmares with the broken toys of childhood brought to life to haunt the girl-come-woman. But it is really about how the innocence in all of us can be destroyed by the beast unless we are able to control it.

Everything works. Much like Guillermo del Toro, Jordan does such a fantastic job of creating the world — the woods, the village, the grandmother’s house — displaying a beautifully Boschian production design like an Alice in Wonderland in Hell with George Fenton’s score incorporating what sounds like a chilling synthetic harpsichord sound throughout. Christopher Tucker’s effects are particularly innovative, having worked on David Lynch’s The Elephant Man and Dune the same year, there is a surreal quality to the work that carries over. This is the peak of animatronics and practical effects we were spoilt by back in the ‘80s; Tucker’s visceral transformation scenes are still unique, even in the wake of Rob Bottin’s work on The Howling and Rick Baker’s Oscar-winning makeup effects on An American Werewolf in London which often overshadow everything else since.

One the unforgettable transformation sequences from Christopher Tucker.

There is this portmanteau quality that provides a seamless collection of tales, told through stories and dreams, as we slowly see this transformation of the girl into womanhood. As Rosaleen continues to dream, Grandmother (Angela Lansbury at 58!) often reminds her (and ourselves): “Once you stray from the path you’re lost entirely! The wild beasts know no mercy. They wait for us in the wood, in the shadow, and once you put a foot wrong, they pounce!” For the most part, she remains on the path of adolescence yet, once strayed, encounters the bestial sexuality of men. Grandmother’s timeless warning is, “A wolf may be more than he seems. He may come in many disguises. The worst kind of wolves are hairy on the inside, and when they bite you, they take you with them to Hell.” [7] The stories are advice, and guidance, passed down from generations, never to be forgotten but baked into your soul.

And in the film’s climax, the wolf bursts in and destroys her childhood room and all its childish things. And a woman is born for better or worse.

1.

La Belle et la Bête (1946)

My number one movie may feel like it flips the script on everything discussed. Some may see this as a cheat, but I am going to highlight the importance of the original “Beauty and the Beast” tale with Jean Cocteau’s La Belle et la Bête from 1946. Hopefully, throughout what has been shared so far, we have all come to realize that the werewolf tale follows this template. There are, after all, obvious parallels.

John Cocteau is one of my all-time favorite artists. If you had to put one word on his gravestone it would certainly be “poet.” Although he was a poet throughout his entire life, having had his first work published as a teenager, he was a polymath working as a playwright, novelist, designer, film director, visual artist, and critic. He only made about a dozen films, from shorts to features, all of which are high art and most starring his long-term lover Jean Marais. Both La Belle et la Bête and Orphée from 1950 are masterpieces and, for me, almost inseparable. They come from the same poet’s heart.

The film was made in 1945, right at the end of World War II. In France at that time, everything was hard to come by and Cocteau had to use second and third-hand cameras and equipment that was already 20 to 30 years old. The cameras kept jamming or breaking and they never had enough film stock; you can see the change in film stock throughout where some shots appear to be grainier. Yet Cocteau knew which stock to use for which scenes and the result is as if he had planned it that way.

Josette Day as Belle and Jean Marais as The Beast/Prince Avenant. It is incredible to think how lavish Cocteau's rendition of the original story is based on what little was available at the time of production.

On top of all this, the costumes were patched together from pieces because there wasn’t enough fabric in France. Times were so desperate that when they would come back to the set in the morning, the curtains in the castle (Château de Raray located in Raray) had been stolen. Then Cocteau was hospitalized in the middle of filming due to a skin disease with René Clément taking over while he recovered. So, while his lover was destroying his own skin under all the makeup for the Beast — Marais’ skin burned due to no solutions back then to remove the appliances effectively — Cocteau was also suffering. Both men were essentially turning into monsters while they were making this fairy tale.

More feline, for sure, and although the film is more artistic than a Hollywood movie, there are certainly shades of the wolf and Universal's influential monsters' designs.

Most of you know the story. A rich merchant with three daughters plucks a rose from a lavish estate on his way home to take to his only loving daughter and the Beast appears saying that he has stolen a rose and the punishment is death. But he tells the merchant to send one of his daughters to live with him. Only then will he spare his life. Of course, the two nasty daughters are unwilling and the pure one takes on the burden because she loves her father and does not want to see the Beast kill him. When she arrives she is submerged into a fantastic and surreal world of the Beast, where statues breathe smoke and the hallways are lit by living arms holding candelabras. Belle comes upon the Beast through a door in the wall, where he is lying on the ground and lapping water from a pond like a lion. He is hideous, but strangely beautiful. Slowly, even as she watches him gorge on his banquet, blood covering his fur, she begins to see the humanity underneath the Beast.

The Beast seems to be what a werewolf would be if he followed a more noble path; where aristocracy has complete freedom and as though the very rules the elite have made turn them into complete monsters. Remind you of anything? Ultimately though, it is about the transformative power of love. As stated at the beginning, true werewolfery is an instinctual drive to kill the thing that it loves, while at the same time, it is only love that can tame the savage in all of us. The interplay between the two is where we live as humans in trying to make our way through the world we have created.

In conclusion, the perfect werewolf movie takes place during a transformation of society when it is ripping itself free of the old shackles and discovering what the new world has in store. But without love at the heart of it, we will never have a successful transformation. The transformation will destroy us… unless it pays honor to and serves the quality of human love, in all its forms.

You can read the first two issues of Renegade Entertainment’s The Lycan here, as part of Comixology Originals. For further news on Renegade Entertainment, you can stay up to date over on Instagram @wearerenegades. You can also follow Thomas Jane on Instagram @cardcarrying_thomasjane X @thomasjane.

References:

1. Further reading can be found via Rich’s Fangoria piece Beautiful Beast: An American Werewolf at 40 from 2021.

2. These undercurrents, along with more on the Darwinian influence, are discussed in great detail via Rich’s Fangoria piece from 2021 “Under A Swastika Moon: 80 Years of The Wolf Man.”

3. Many monsters carry the Jewish stereotypes such as witches and their hooked noses and, it could be said that even those who perceive Jewish men as hairy fit into the stereotype of the werewolf. They are “othered” by latching onto a particular appearance; made to feel as though they are a dog; the persecuted lower than animals. Antihuman.

4. In The Lycan, we also have an American outsider from the colonies with his wild bunch of professional hunters in tow, all of whom are unchained from the roles assigned in society. As Sailors they are classless and have no traditional employment; simply a tight-knit group of adventurers who have each other’s backs. We see what they have captured on their way back from Africa with tigers in the hold, establishing how good they are at their job. Now, stepping into this foreign (and alien land) they quickly discover it has a wolf problem, with the villagers now holed up in a fortified castle that is now a convent, run by a sect of nuns. And at the same time, we have the redcoats who have stationed themselves there to protect the nuns, sidetracked from a mission.

5. McGilligan, Pat, ed. Backstory 2: Interviews with Screenwriters of the 1940s and 1950s, “Curt Siodmak: The Idea Man,” Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991. pp.246-273.

6. Anthony Hopkins’ Sir John Talbot also turns out to be the original Wolfman. There are problems with the story — and obviously a problematic production — but despite Rick Baker’s work being sidelined somewhat you can still detect his influence on the transformation sequence in the insane asylum, which employs some excellent use of CGI emulating the physicality of his practical effects as close as possible.

7. Similarly to The Curse of the Werewolf, there is also a throwaway line of never trusting a man born on Christmas day.

Comments